A few years ago, I received from a missionary couple an ESV copy of the Gospel of John—yes, just the Fourth Gospel—which is often distributed for evangelism purposes. The assumption is that the Gospel of John is the best entry point for meeting Jesus and reading the Bible. I don’t know all the reasons why, but I find this both puzzling and intriguing. Maybe it’s because the Gospel of John so richly encompasses the whole story of Scripture and can encourage new readers to engage more deeply with the Bible. But on the other hand, have you ever noticed how many times the Gospel of John mentions a Jewish feast or makes an allusion to the Old Testament without citing it specifically? I would argue that the Gospel of John is the most Jewish of the Four Gospels but draws from the tradition to reinforce the centrality of Jesus for Christian worship. For new readers of the Bible, this may present a challenge or pass by unnoticed, but it presents a great opportunity in discipleship to revisit the Gospel of John as a lens for reading the whole Bible.

So, here’s the big idea: In John’s Gospel, Jesus redefines through his own mission of redemption the Jewish feasts celebrating God’s deliverance. As the Light of the World, Jesus sets the rhythm for worship and he is the object of worship.

The Creation Origin of Festivals

Now, you might be thinking, “Wait, isn’t this is a series about the theme of creation in the Gospel of John? Why are we talking about the festivals in ancient Israel?” Well, first of all, Genesis 1:14 depicts the sun and moon like sacred lamps in a cosmic sanctuary calling humans to worship: “And God said, ‘Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate the day from the night. And let them be for signs and for [festivals], and for days and years.’”

The word moadim in Genesis 1:14 is typically translated in the Old Testament as “religious festivals” or “sacred times,” not seasons of the year like fall or winter. In Leviticus 23, we see the common usage of moadim/festivals when the Lord prescribes Israel’s feasts":

The Lord spoke to Moses, saying, “Speak to the people of Israel and say to them, These are the appointed feasts [moadim] of the Lord that you shall proclaim as holy convocations; they are my appointed feasts.” (Leviticus 23:1)

Then it lists these feasts:

Sabbath

Passover

Firstfruits

Feast of Weeks

Feast of Trumpets

Day of Atonement

Feast of Booths

For ancient Israel, then, the fourth day of creation depicting the heavenly lights marking their religious festivals reinforces that their rhythms of worship are not an arbitrary invention but are written in the fabric of the universe.

Second Temple Reimagining

Following the Babylonian exile, the feasts had taken new meaning centered around the building of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. In John’s Gospel, however, Jesus is asserting himself as the true Temple. After all, these feasts were meant to celebrate God’s presence with his people after delivering them from Egypt, and Jesus now embodies God’s dwelling presence and identifies himself as the promised Savior (John 1:14).

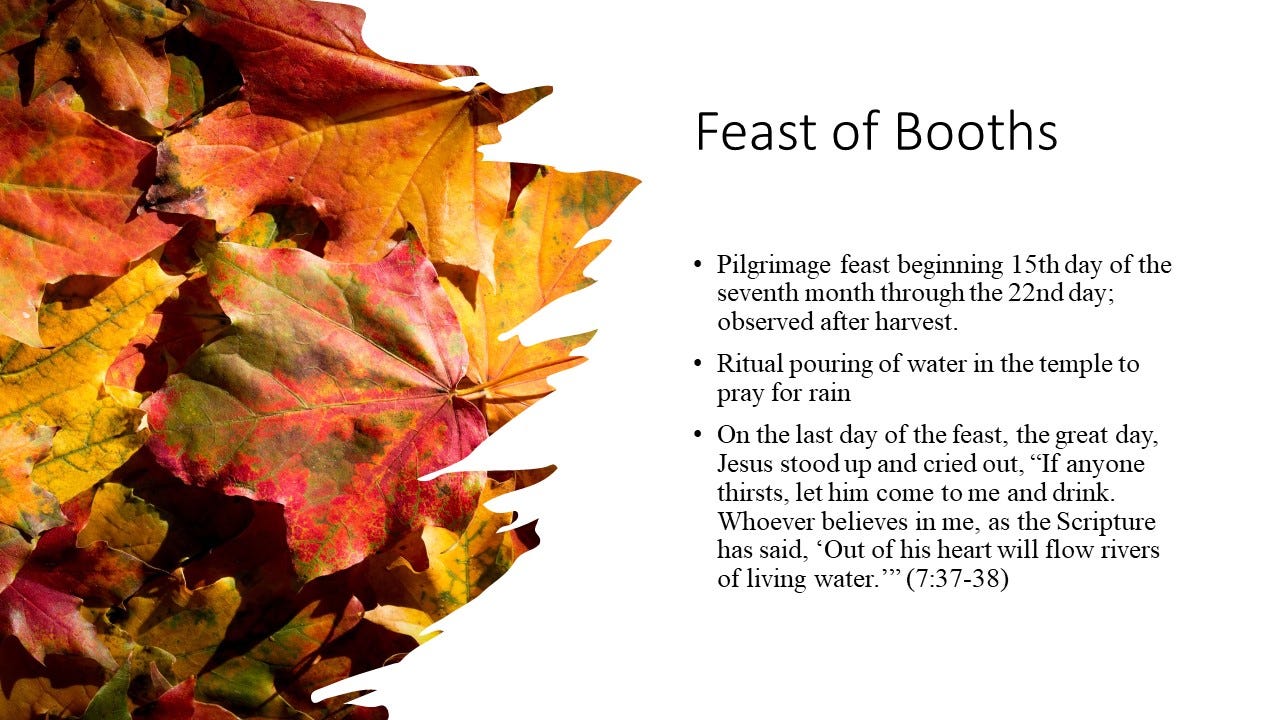

We can see, for instance, how the Festival of Booths, became a pilgrimage feast to Jerusalem after Nehemiah reconstituted its observance during the rebuilding of the temple (Nehemiah 8:13-18). Apparently, even though the festival is listed in Leviticus 23, it had not been celebrated since the wilderness generation. Its connection with Jerusalem and the Second Temple intensified when the postexilic prophet Zechariah said this about the festival:

“Everyone who survives of all the nations that have come against Jerusalem shall go up year after year to worship the King, the Lord of hosts, and to keep the Feast of Booths. And if any of the families of the earth do not go up to Jerusalem to worship the King, the Lord of hosts, there will be no rain on them.” (Zech 14:16-17)

With this prophecy about Booths, Zechariah is also speaking of a messianic King who will have authority over all the nations of the earth. As we will see, Jesus interprets the Festival of Booths around himself and discloses the meaning behind “the rain” promised to those who worship him.

Jesus Fulfilling the Feasts in the Gospel of John

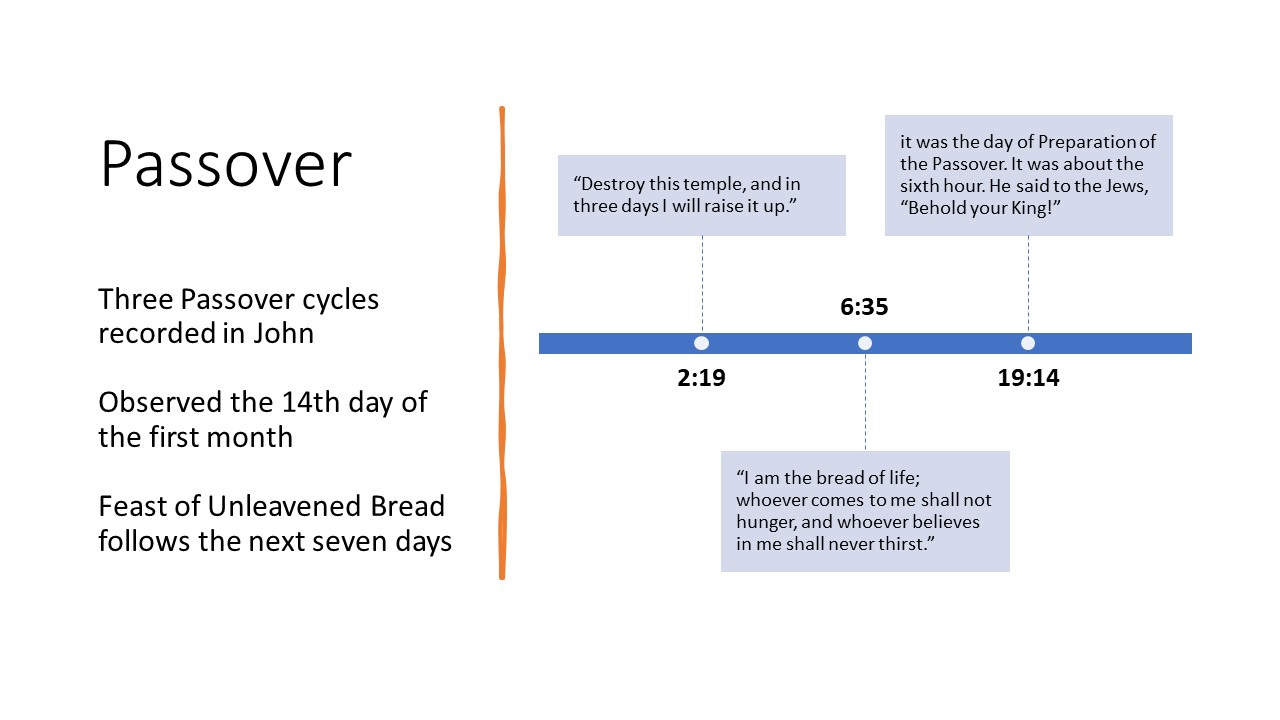

John’s Gospel uses the Jewish feasts as a plotting device, beginning with a Passover in John 2 and culminating in a third Passover at the crucifixion in John 19. The Fourth Gospel is so meticulous about its plotting, noting the days or feasts on which a story occurs, that some scholars have tried to speculate a significance to the number of days counted in a particular passage (John 1:29-2:1) or the total number of feasts. For this lesson, however, I am focusing on just three feasts which occur in the Gospel: Passover, the Feast of Booths, and the Feast of Dedication. Later in this series, I will discuss the Sabbath healing episodes, including one that occurs on an “unnamed feast of the Jews.”

Passover is the first feast that appears in John’s Gospel and is the most significant theologically for his presentation of Jesus. The Passover originated in Exodus, when Israel was delivered from Egypt. In Exodus 12, the Lord instructs Moses and Aaron to tell the Israelites on the fourteenth day of the first month to sacrifice a lamb, paint the doorpost with its blood, and eat it, with the blood serving as a sign for God to “pass over” them when he strikes the firstborn of Egypt. They are to continue this feast as a “statute forever” and also to observe the Feast of Unleavened Bread for seven days from Passover until the twenty-first day of that month. Passover was not just a memorial to the past of God’s deliverance and provision but a living promise of God’s faithfulness and protection.

In the context of John’s Gospel, Passover had become a pilgrimage feast to Jerusalem. Jesus, as a faithful Jew, went up to Jerusalem for the feast, but it also happened that he entered the Temple and overturned the tables. When confronted, Jesus says, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up” (John 2:19). He is talking, of course, about his body and foreshadowing his crucifixion and resurrection. But notice too that he is identifying himself as the true Temple, the dwelling place of God. The deliverance that began in Egypt with Passover culminates in the dwelling of God in the wilderness Tabernacle. But Jesus is starting to redefine the meaning of this central feast around his mission of redemption.

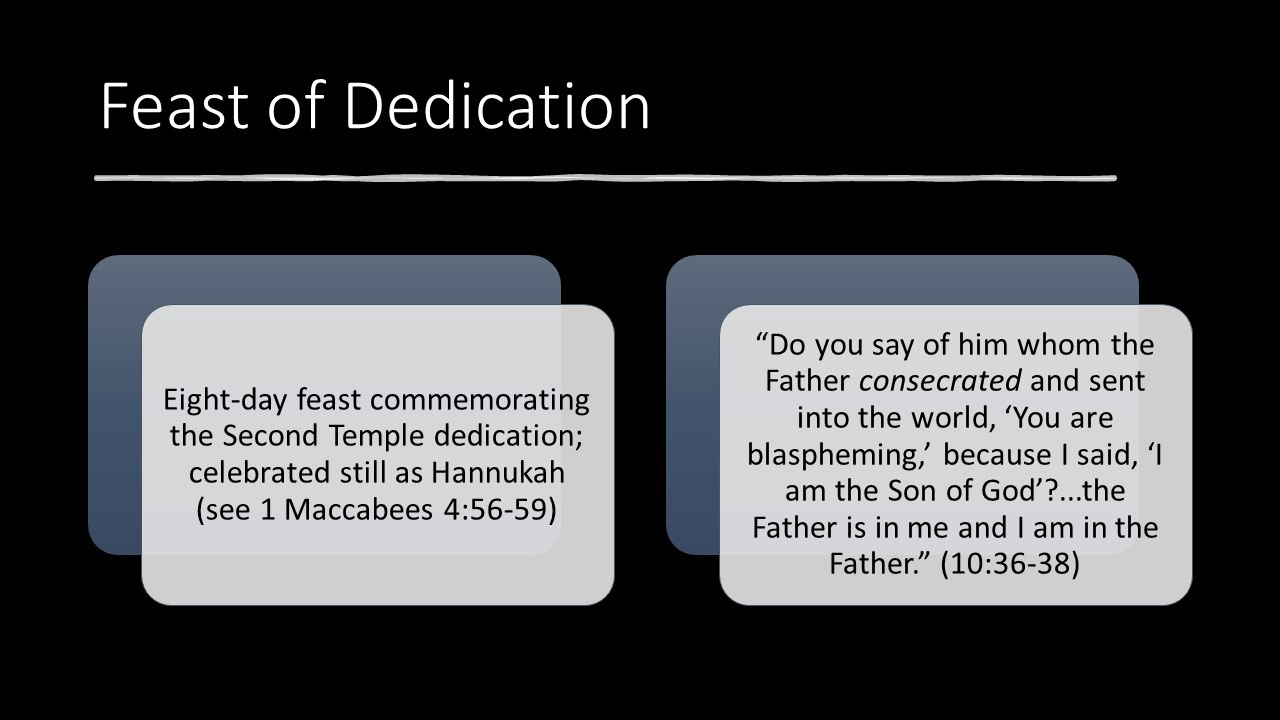

Skipping ahead of the sequence but keeping with the theme of the Temple, let’s look at the Feast of Dedication in John 10. This feast we know as Hanukkah, and is still celebrated today. But we find its origin in the second century before Christ’s birth during the Maccabean revolt against pagan influences. After the Temple was ransacked, one small jug of oil was left and when it lit the lamps it lasted for eight days. The miracle affirmed their belief that God had consecrated this temple. In 1 Maccabees 4:56-59, we read of the celebration of the Feast of Dedication, lasting for eight days, and later in 2 Maccabees 10:16 the gladness with which they celebrate is compared to the Feast of Booths.

So, in John 10:22, we find Jesus in Jerusalem observing the Feast of Dedication. When he reveals himself to be the Christ, and one with the Father, he is threatened with stones. Jesus responds, “Do you say of him whom the Father consecrated and sent into the world, ‘You are blaspheming,’ because I said, ‘I am the Son of God’? . . . the Father is in me and I am in the Father (10:36-38).” Notice the language he is using here. At the Feast of Dedication, commemorating God’s blessing of the Second Temple, Jesus is identifying himself as consecrated by the Father. And then Jesus departs the Temple, and in John’s Gospel he never returns.

It’s important to note that John’s Gospel was likely written later in the first century, around AD 90. In AD 70, the Second Temple was destroyed, and Jewish worship scattered and reorganized around synagogues. But John’s presentation of Jesus shows that early Christians had already adapted around the true Temple of Christ.

Now we can revisit the second Passover, recorded in John 6. Notice now where Jesus is. He’s not in the Temple to observe the feast but by the Sea of Galilee, where he feeds the five thousand. And in another image from Exodus, Jesus refers to the manna from heaven in the wilderness, saying it was not Moses who gave Israel the bread from heaven but the Father. Even more shockingly, Jesus says, “I am the bread of life.” Through him we can live forever. But just like in the first Passover, this statement also points us toward the cross.

The Feast of Booths in John 7 is also highly significant in John’s Gospel, but I will spend more time here in the next lesson. As I mentioned above, this pilgrimage feast became connected with agriculture and praying for rain. Jesus promises living water, just like to the Samaritan woman at the well. The statement that, “Out of his heart will flow rivers of living water,” has a twofold meaning (John 7:37-38). In one sense, it references the water that flows from his side on the cross. Living water taking away our sin. But it also tells of the Holy Spirit, living water, who gives us new life. John the Baptist said of Jesus that he baptizes with the Holy Spirit, connecting water with the outpouring of the Spirit. So Jesus is unfolding the prophecy of Zephaniah, in which he is the exalted King of all the nations and pouring out on those who worship him the living water, the indwelling Holy Spirit.

Finally, the third Passover, which John’s Gospel signals is coming in John 11, culminates in the crucifixion in John 19. In fact, the Gospel has been preparing us for this moment ever since John the Baptist declares, “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29). In John 19, we read Jesus was handed over to be crucified at noon on the Day of Preparation for Passover. Since this Passover feast fell on a Sabbath, it was a great Sabbath, and so all the lambs had to be sacrificed before sundown. And because Passover was celebrated in Jerusalem at the Temple, the priests began slaughtering the lambs at noon.

All throughout John’s Gospel, we see Jesus redefining the significance of the feasts around his redemptive mission. He is the true Temple, the Bread of Life, and the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world once for all. At the climax of the Fourth Gospel, Jesus becomes the new Passover Lamb, whose body feeds and whose blood redeems all who draw near to him. Jesus is the object of worship, the Light of the World, and our rhythms of worship orbit around him in the celebration of the Eucharist on the first day of the week—the day of his resurrection.

Thanks for this whole discussion, I've never noticed the overall Festival plot in John's gospel before and this is fascinating. Especially thinking about some commentators who will say John's Gospel is "unsacramental" because it lacks a Last Supper narrative and doesn't narrate Jesus' baptism to the same extent as the synoptics. This outline on the 3 Passovers is a strong and clarifying pushback to that!

Just to follow up on your first section, I've heard the same about the Gospel of John and missionary work. I remember one book that basically promised "if you read through the Gospel of John with non-Christians, they *will* become Christian." I've always found this surprising too!